Régimen II, semana cero

The new pills didn’t come in a small, yellow, circular case that denotes its use. This brand provided an envelope-like blue container that looks like the cover of a pad to take notes in. If someone were to see me take it out of my purse, they wouldn’t know what I was doing: maybe writing down a new, brilliant idea. I should have known everything would go to shit with the new pills. Since the moment I saw the little blue envelope, I thought of how they might be a cheap knock-off of my old brand, but I tried not to feel disconcerted. I thought of the doctor’s golden promise of them being cheaper than the $32 I used to spend. $32.37 dollars later, I barely had the balls to ask the pharmacist about the price; her ensuing expression almost looked insulted. She pursed her gas station bubble gum pink lips and eyed me with disapproval: “Es más barato que un hijo”. If it hadn’t been for fear of unsettling the older woman who had been chatting me up about Monica’s gold medal, maybe I would have also had the balls to give the pills back and wait to consult my doctor. But I felt the pressure of the pharmacist’s heavily eye-lined gaze and the crushing paranoia of that 2% that condoms don’t protect against. It hadn’t been five minutes since my departure from the Walgreens counter, when I sat in my little car and held the little blue envelope between my dejected hands while I cried.

Régimen II, semana uno

The Walgreens debacle aside, I focused on irradiating positive vibes towards the little blue envelope. I don’t usually bother with things like these, for I'm a self-proclaimed paranoid pessimist, but I thought that the $32.37 had to be worth something. I didn’t notice the side effects immediately, but they eventually came in waves, like grief, the grief of my body rejecting birth control. I started suffering from drastic mood swings, and every time I bothered to eat something I felt like the food had taken up permanent residence in the bottom of my stomach. Gas seemed to fill out every crevice in my intestines (more on this later, although the masses disagree with the idea of women having bodily functions). I originally attributed the moods to troubles with my job, anxiety about money (or lack of), and persisting difficulty I have with overcoming old grudges. All of this, coupled with the recurring physical discomfort, accumulated a steady sense of desperation. I sat in the corner of my bed and tried to reason myself out of the daze I was in. On my computer, I tried to budget my way out of my irresponsible spending, but all I could do was stare at the $32.37 and the $25 I didn’t have for a pregnancy test for my doctor. For the first time, I thought about how difficult it was to be a woman in the medical world.

Régimen II, semana dos

Régimen II, semana dos

"Tratando de mantener mi estabilidad emocional y otros asuntos, una crónica”, I wrote on Twitter during the second week. I was already attuned to the pill’s involvement in my unstable life state. I thought of the reminder I’d set for every day at 8:00 PM for when I took my pill: “No flaquees”. My mother told me to stop taking them and I thought about the $32.37. Every day I suffered an upset stomach; I felt the hostility sweating through my pores as I walked through campus or sat back on my bed trying not to lose my calm. I repeated the key terms to myself: “$32.37. No flaquees”. One day that I was considering my precarious situation, I remembered how the doctor had told me everything would go well, in that untroubled doctor tone, before leaving the exam room. I thought about the pharmacist with her pursed lips. Maybe the pills were cheaper than having a kid, but what I wasn’t paying for a kid was costing a tenfold to my body.

Régimen II, semana tres

You know how they say, that before a terminally ill patient passes away, they experience a week, or maybe a day, in which they miraculously seem cured? I’ve read that they call it “the one last good day”. Well, the third week on the pills, I had a "few last good days".

Régimen II, semana cuatro

Iwas five days away from finishing the pack. That Tuesday, I felt the characteristic heaviness in my stomach that had accompanied me for sixteen days since I’d purchased the little blue envelope. Before having dinner, I took the necessary precautions to avoid any further discomfort, but the green Gasex pill felt as effective as having accidently swallowed a wad of gum. At one in the morning, I dragged myself towards the bathroom in need of a possible place to deposit my dinner. As I cradled the toilet between my hands, my dog found me resting my head against the seat. Her eyes told me she was dying to investigate what I’d conjured in the water, but I only pushed her away. At two, I visited the bathroom again, but this time, after flushing the toilet in dejection, I grabbed the blue envelope and sunk it in the trash.

Semana uno

Ididn’t throw away the pack. The little blue envelope is actually on my dresser, because I’m terrible at throwing things away, and I like to be reminded of bad things that occur in my life. Every time I see it, I think of that brilliant idea of a twenty-one-year-old girl trying to be a responsible woman, paying 32 dollars to receive a blue envelope, and instead signing away her peace of mind and body. I figure next time she sits in the exam room and the doctor tells her "it’ll go well this time", she won’t trust her, and she’ll be staring anxiously at the price, wondering if she’ll find herself cradling a toilet seat at two in the morning, regurgitating her hopes of avoiding that 2% gap. She hopes the next time around, she won’t need a little blue notebook to write a sad idea down. She’ll have the envelope around to remind her, after all.

Lista de imágenes:

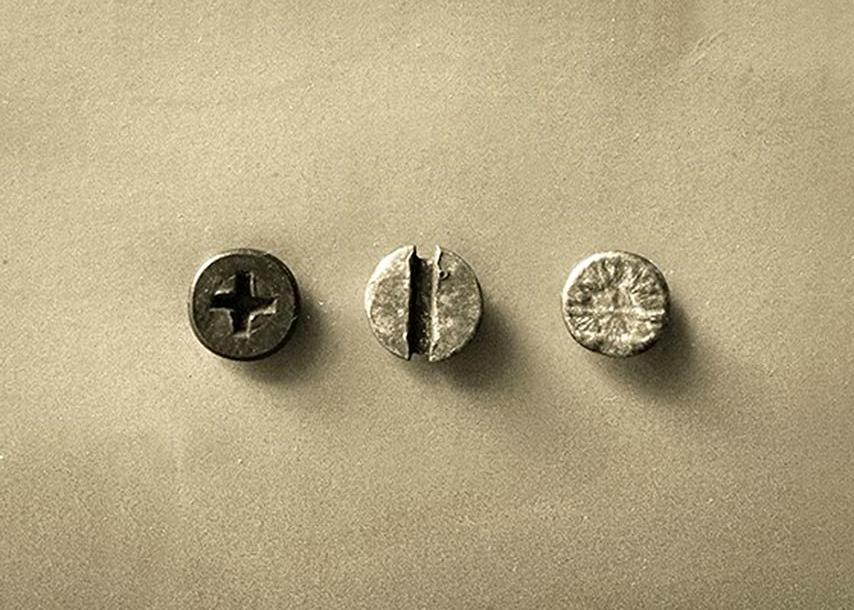

1. Ata Mohammadi, Repulsion

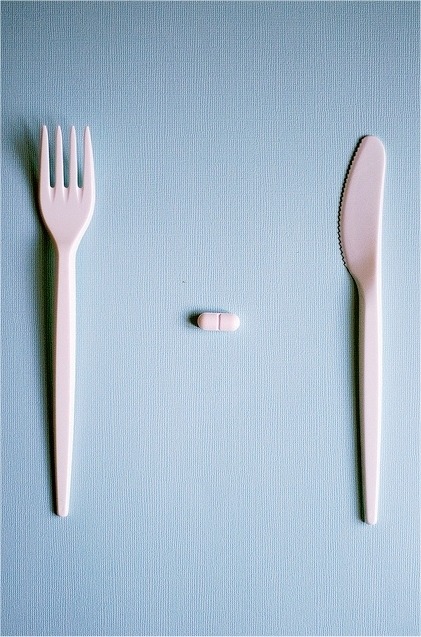

2. Straccetti, 2011