“…and as i began to disappear

i realized, someone was beginning to forget me.”

-ADÁL

"What is surreal is the distance imposed, and bridged, by the photograph:

the social distance and the distance in time."

-Susan Sontag

Born in Utuado, Puerto Rico in 1948, Adál moved to the United States as a child, with his mother, during the first decades of a massive migratory movement openly incentivized by the United States and the Puerto Rican colonial government, as part of a socio-economic development plan for the Island. Like many Puerto Ricans, Adál’s mother migrated to Patterson to work in a factory. There, in the new land, Adál met a neighbor who introduced him to the techniques of photography development and the dark room experience for the first time when he was between 10 and 12 years old.

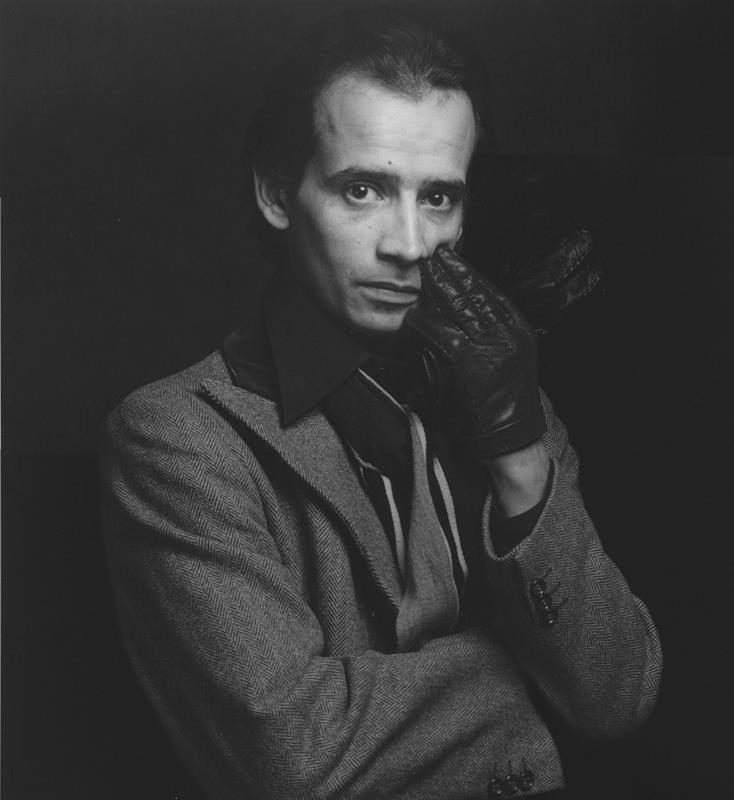

Portrait of ADÁL by Robert Mapplethorpe, 1979.

Arriving in New York at the age of 17, Adál enrolled in the Grace Dodge Vocational High School where, during his last year, he had the opportunity to be hired as the assistant of Harold Greer, Bert Millers and Charles Stewart, an African American photographer famous for his photographs for some jazz album covers. These photographers gave Adál the push and the initial financial aid to study at the Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles.

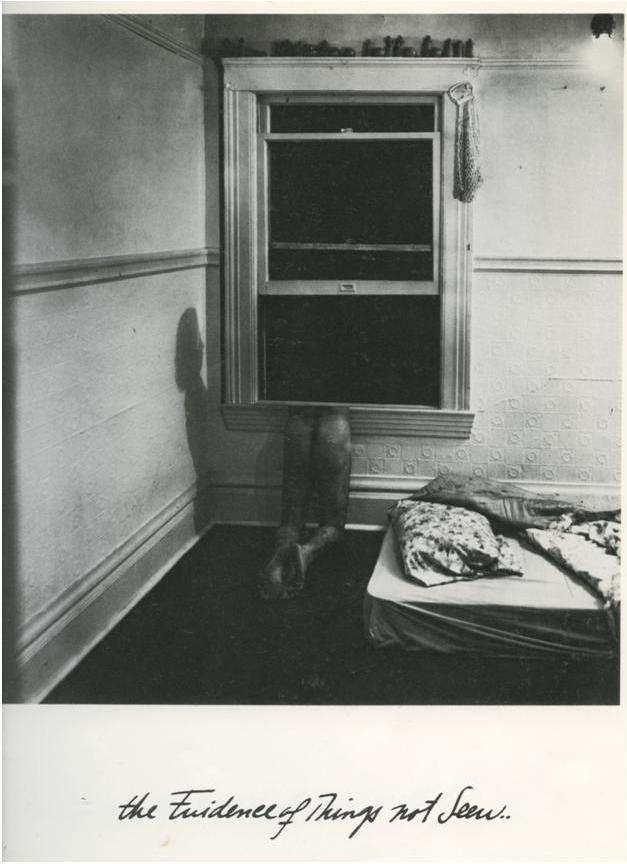

Impacted by migration, displacement and marginalization during a historical moment of intensive social activism through the United States, Adál developed a high sense of critical thinking that he showed in his early work as an artist. The Book “The evidence of things not seen” is Adál first publication, and contains a series of photographs exhibited in San Francisco, California at La Raza Gallery in 1973.

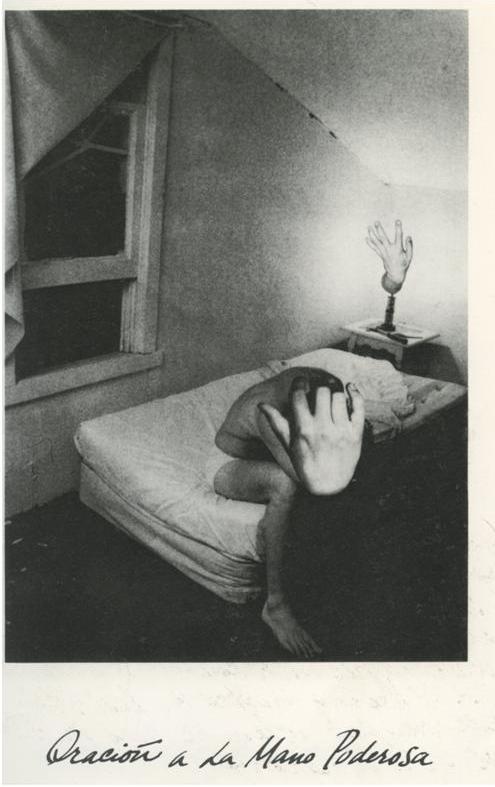

“Oración a la Mano Poderosa” [A Prayer to the Powerful Hand].

As an introduction to this book Adál wrote:

“If you come across a grill on the pavement and see your shadow cast into it, then tell me that the shadow represents you and the shadow’s entanglement in the grill your entanglement in life, i’ll probably agree with you, the same as i’ll probably agree with another to whom the same image may remind of having dropped his last token into a pavement grill, one day, when he was on 42nd street and hat to get up to the bronx…”[1]

In “The evidence of things not seeing” Adál demonstrates a deep understanding of the relation between art and thinking. This artist shows a profound capacity to conceptualize and to theorize through the uses of image and text, building visual metaphors and juxtaposing the interpretation with the literal meaning.

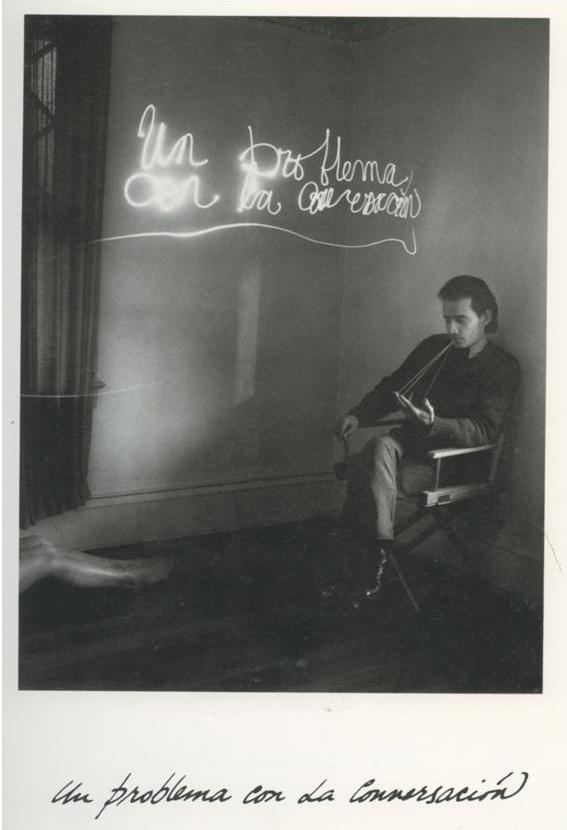

Adál refers to spoken language as a structure to understand life. Both English and Spanish are used to defy the photographic images he conceptually produces.

But, interestingly, in the same body of work, the challenge is subverted. The language, as a referent for thinking, as a structure for ideas and for reality to be understood, can be defied also by a photographic image and it’s interpretation.

In both cases, Adál defies the connection of the photographic image as a truthful representation of what is real as much as the language as a truthful representation of what our ideas are.

In the photograph “Oración a la Mano Poderosa” [A Prayer to the Powerful Hand] the image is defied by the text as a reference of what we know. The relation of a godly hand as a Santería symbol is subverted and the power is related to the physical hand of the individual, relating its meaning to writing and artistic creation as spiritual and emotional processes.

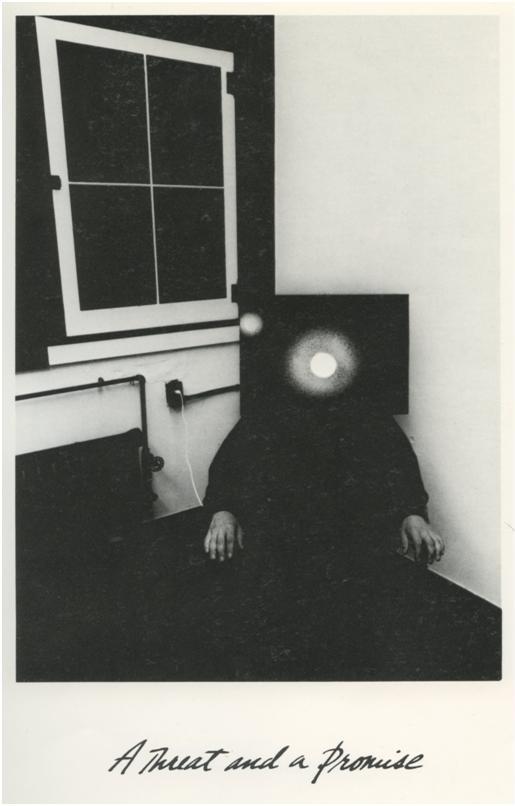

"A Threat and a Promise."

About this body of work Thomas Albright published a review in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1973:

“Maldonado works with images in a symbolist surrealist fashion which I have grown to hate because so many photographers, and painters, have been playing around over the surface of this territory to such superficial and contrived effect. Maldonado is one of the few artists I’ve seen in a long while who really drills down deep inside”.[2]

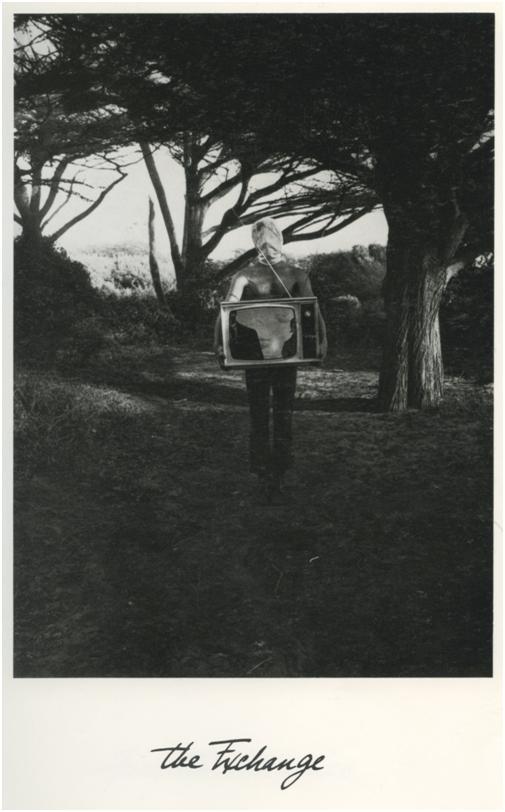

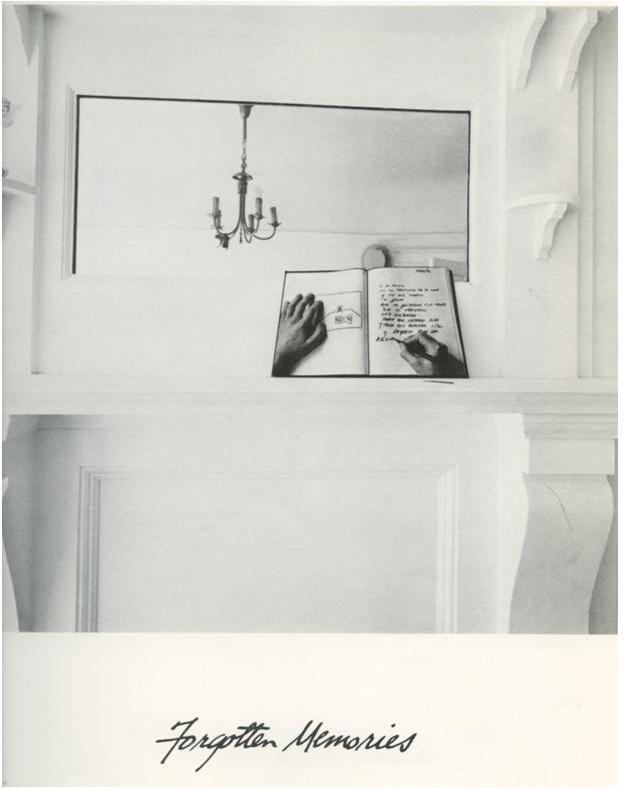

"Forgotten Memories."

Highly influenced by Surrealism and Neo-Dada, by “Duchamp, Luis Buñuel and Jorge Luis Borges”, but particularly by his condition as a migrant and as a Puerto Rican, Adál faces his reality in a convulsive world as an artist and as an individual: “[…] So to my great surprise, my experience as Puerto Rican made me a surrealist without knowing it. […] However, my dada and surreal influences have always been filtered through my personal experience”[3], he says.

"The Evidence of Things not Seen…"

Adál uses spoken and visual languages as complementary structures to connect the spectator with ideological and discursive constructions:

“All my work is connected by three threads. One is a concern with the conceptual, the other with identity issues and the last is a concern with the integration of text. My intention is for the text and the image to be independent of each other but when you see them together to create a third space or reality. These are sources that I return to over and over.”[4]

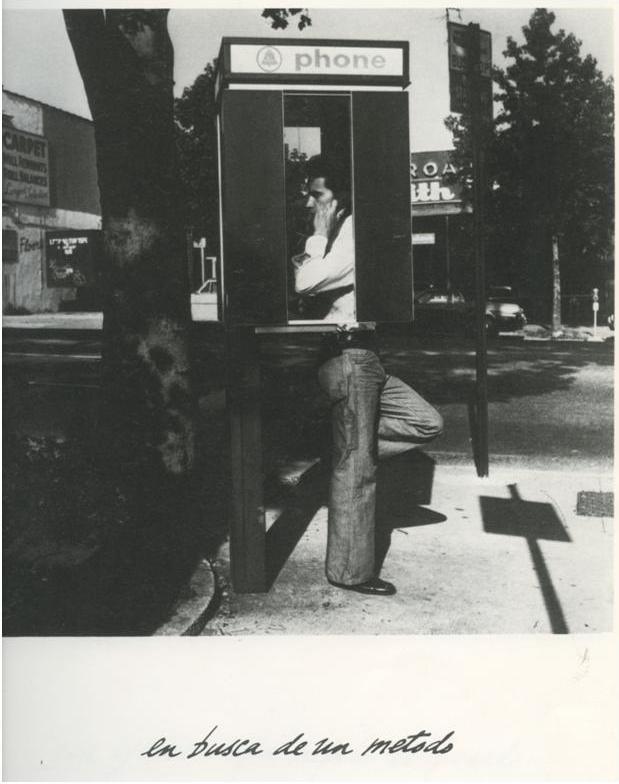

"En busca de un método" [Looking for a method].

This body of work reveals a self-reflective artist that questions the tenets of modernity, using avant-garde tools in a personal rapprochement with art and photography. Adál re-signifies what the probable can be, while at the same time he proposes new meanings to it.

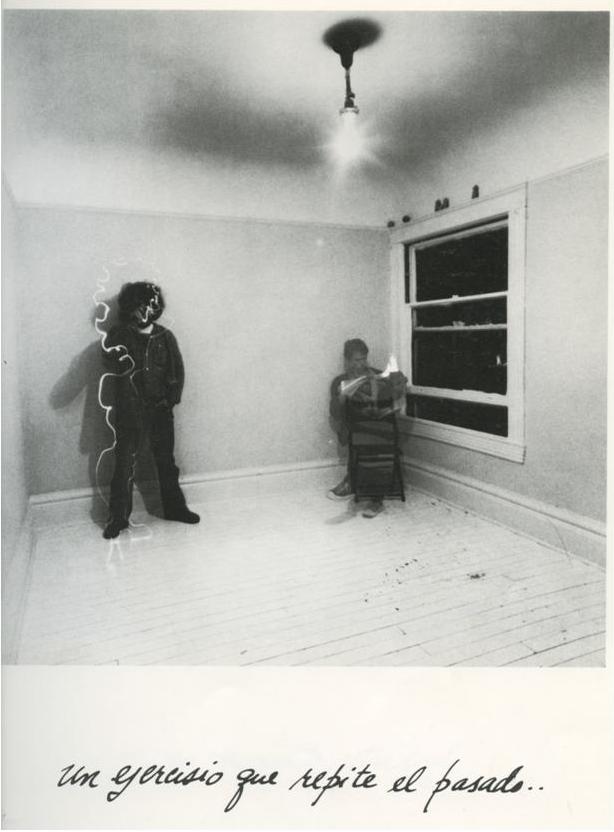

"Un ejercicio que repite el pasado" [An exercise that repeats the past].

Through these photographs, Adál proposes a re-evaluation of the way culture and society understand themselves, a reflection about the way life is lived in the modern society, and a self-reflection about the individual and the role he has or he pretends to have.

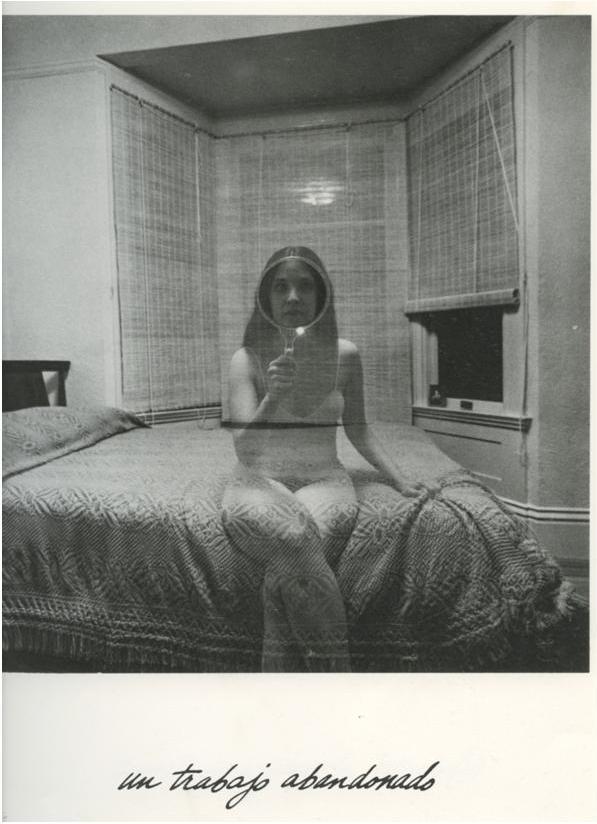

Un trabajo abandonado" [An abandoned work].

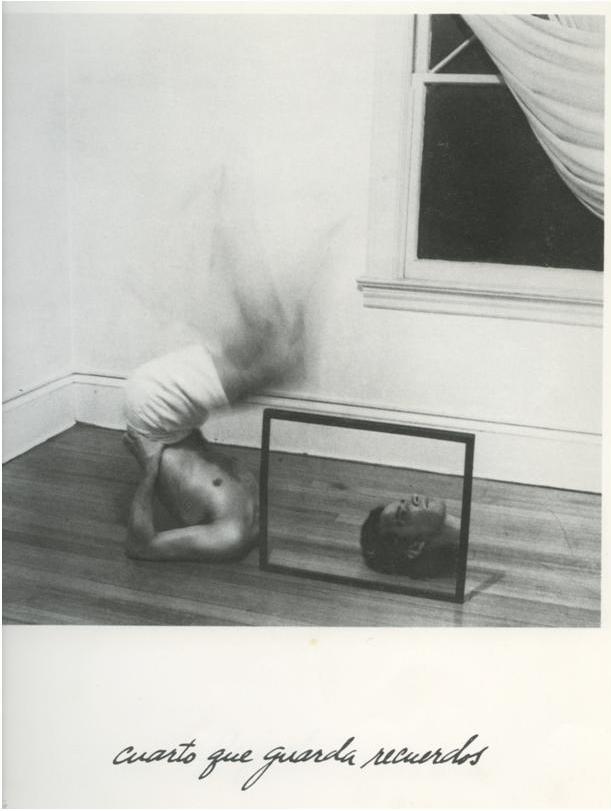

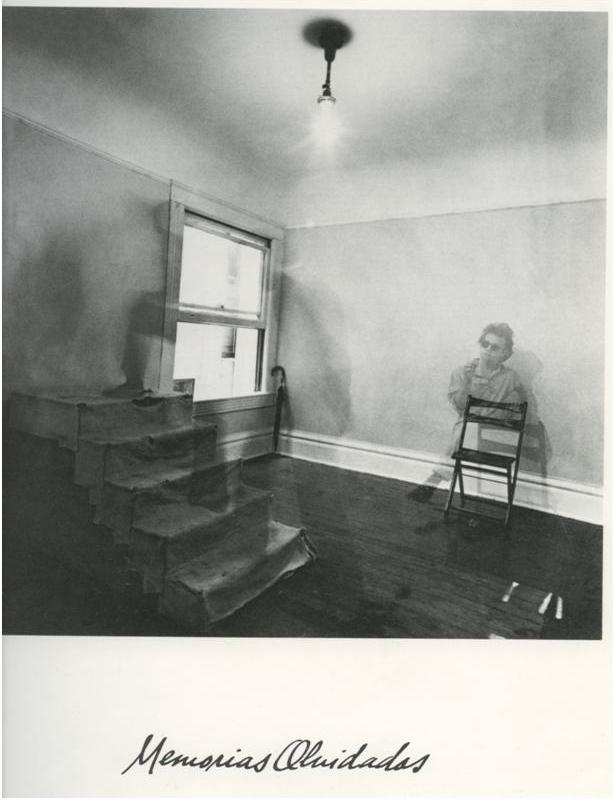

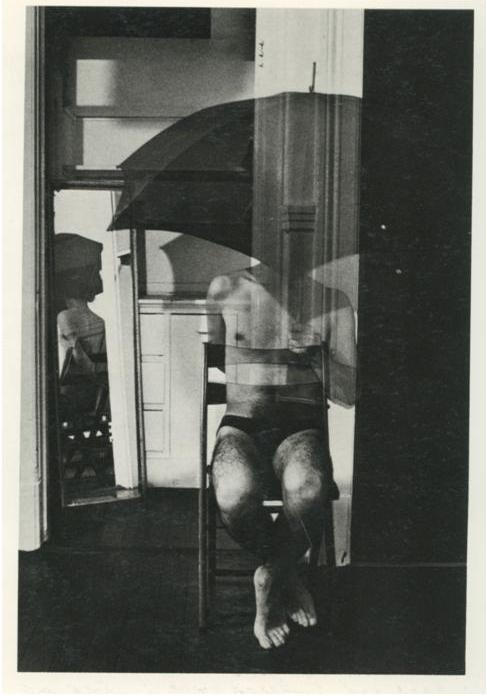

Interestingly, most of the images of this photographic series contain bodies that have been fragmented by the frame, body parts or bodies disappearing in front of the camera using collage or photomontage as formal techniques.

"Cuarto que guarda recuerdos" [A room to keep memories].

This visual narrative, influenced by the aesthetic of the Dada and Surrealism avant-gardes, appeals to the subject as a metaphor of the state of mind: a troubled state of mind divided between the self and the modern constructions of reality:

“The Works that make up my first book, ‘The Evidence of Things not Seen’ were ideas that came to me as a result of a personal experience, a need to work through some existential crisis or a reaction to news stories real or imagined. Once I had a clear concept and an image appeared in my head i would sketch out a drawing. After that I would get the props and the subject which was always me. Those images -for the exceptions of the portraits of famous photographers and critics in the back of the book– are self-portraits. I would put the camera on a tripod with a self-timer, take my picture, take the other images I would need to complete the final work, print all the images and then carefully cut the images and paste them according to the initial sketch I’d made.”[5]

"Un problema con la conversación" [There’s a problem with conversation].

"Memorias olvidadas" [Forgotten Memories].

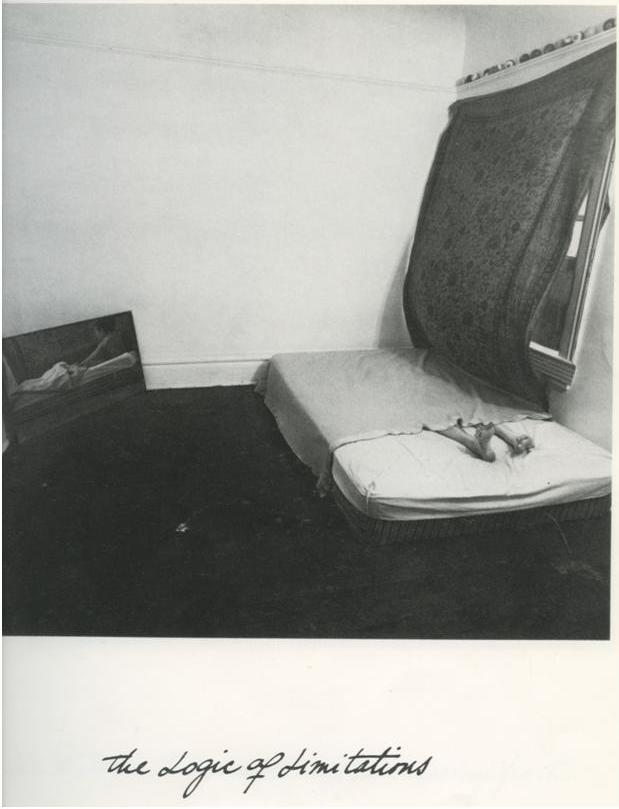

"The logic of limitations."

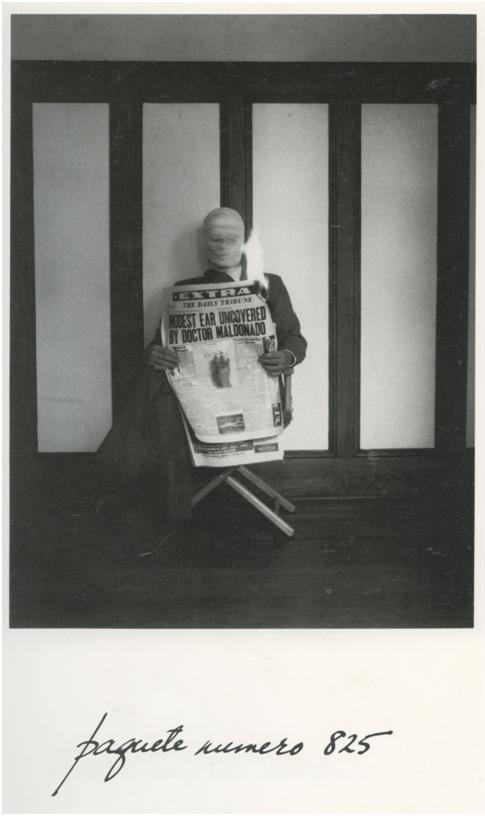

"Paquete numero 825" [Package Number 825].

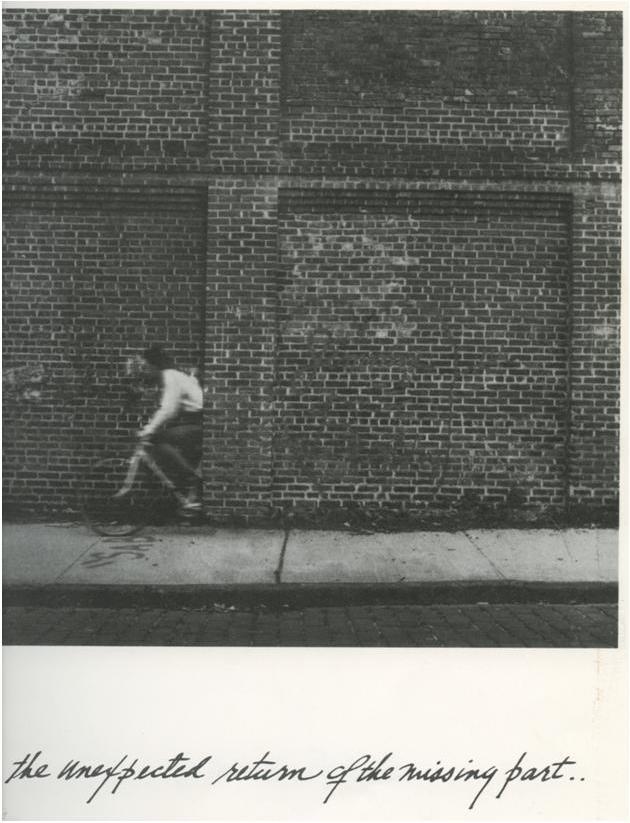

"The Unexpected Return of the Missing Part..."

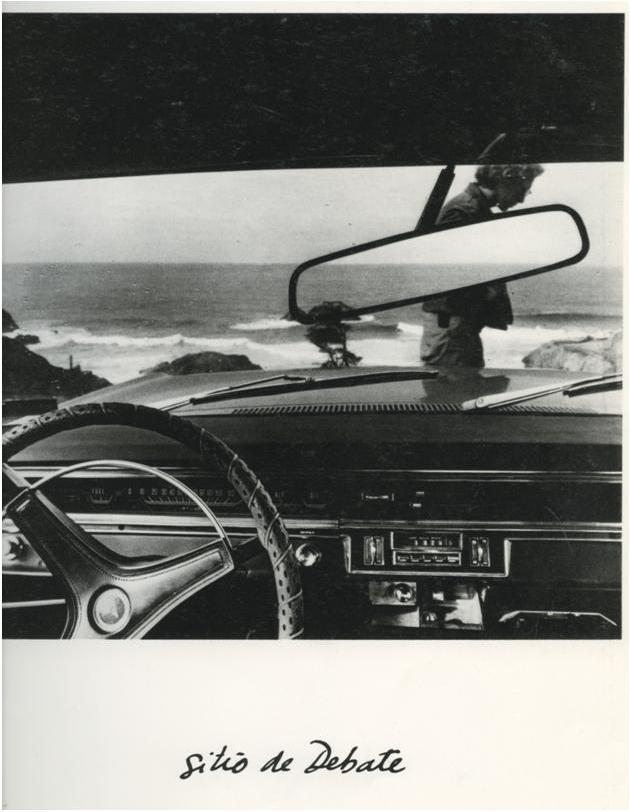

"Sitio de Debate".

"Sitio de Debate".

"Sitio de Debate" [A place for debate].

As a last image that closes the book, Adál presents a man, sited in an interior space, partially nude and holding an open umbrella. The body is disappearing, but the image in the mirror placed on a corner, remains.

" …and as i began to disappear i realized, someone was beginning to forget me."

In the next page, a text proses “…and as i began to disappear i realized, someone was beginning to forget me.” Adál, using a surrealist approach, points to the contradictions of the real and the unreal, and its relation to representation... as we can know it or as we think we know it.

Notas:

[1] Maldonado, Adál, The evidence of things not seen, (New York, New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1975).

[2] Thomas Albright, Art Review, The San Francisco Chronicle, (San Francisco, California, 15/03/1973).

[3] Raquel Torres-Arzola, Interview to Adál Maldonado, (August-September, 2012).

[4] Raquel Torres-Arzola, Ibid.

[5] Raquel Torres-Arzola, Ibid.