Comentando desde el inglés auto-infligido y/o Preliminary Evocations in Claudia Rankine’s Citizen

Luego de más de cinco años en la selva cuasi-laboral, este semestre regresé a la Universidad de Puerto Rico para finalmente concluir los estudios de literatura en inglés. Por razones diversas, la inconexa experiencia estudiantil me recompone como una esencia paradójica. Quizá lo más raro de todo es que admito que el inglés nunca ha sido mi idioma favorito para conversar (siempre me he sentido alienado de mi propia voz cuando lo hablo), pero leerlo y escribirlo me envuelve en una gesta genuinamente meritoria. Pienso específicamente en mi clase de Writing about literature, donde me he enfocado más en escribir que en hablar. Tener la oportunidad de salir de mi contexto idiomático emocional, y encaminarme así a comentar sobre libros-otros en el idioma mismo que éstos se escribieron, ha probado ser un estimulante reto de constricción ensayística.

Entonces el presente escrito —cuya versión original fue precisamente producto del proceso de escribir about literature— hago público mis pensamientos preliminares sobre un libro cuya existencia era para mí desconocida antes de comenzar el semestre. He leído muchas cosas desde agosto, por lo que escoger escribir sobre este libro, en lugar de escribir sobre cualquier otro, es patentemente arbitrario. No es casual que el libro en cuestión es uno que disfruté muchísimo, tal vez por eso es que lo comparto, pero igual pude haber escrito sobre cualquier cosa. Similar al sílabo de una clase itinerante, la finalidad de la existencia estudiantil no recae en la culminación sino en el proceso. La literatura, sea buena o mala, nunca debe ser asimilada sin respondérsela.

En mi intento de canalizar una descentralización consecuente, de aquí en adelante me sumerjo en un English auto-infligido. Más allá de las exigencias estructurales de la clase, más allá de rellenar un requisito que conllevará a mi subsiguiente graduación universitaria, tengo que asumir el constraint, y por lo tanto intentaré potenciar mi presente distanciamiento formalista hacia la construcción de un essay evocador y encaminado. Todo esto es muy pretencioso de mi parte: creo que ya más o menos se concreta mi retorno universitario.

__________________________

With her book-length exploration of the various ways race and discrimination inform the culture of the United States, Claudia Rankine’s Citizenproves to be much more than the sum of its parts. The necessarily disjointed nature of the text not only incorporates different literary modes (mixing poetry, social essays, autobiography and even film scripts) but also works as what literary theorist Gerard Genette defined as transtextuality. Much more than mere references or citations, Rankine weaves superficially disparate artists into her work, creating a series of extremely evocative correlations. Though I’m sure there are others I’ve missed, I thought about four specific authors while first reading Citizen: Marcel Proust, Judith Butler, James Baldwin and Chris Marker.

I’ll begin my extremely brief, yet I hope still concise, reading of Rankine as a transtextual weaver by looking at the very beginning of her book, where a literal awakening takes place. Citizen starts with a first-person narrative of the interchangeably distancing and/or comforting effect of waking up on any given morning. Much like the opening lines of Swann’s Way, the first book of Proust’s massive In Search of Lost Time, Rankine develops a style of poetic prose that’s extremely evocative. There’s an aesthetic kinship in passages such as:

“This impression would persist for some moments after I was awake; it did not disturb my mind, but it lay like scales upon my eyes and prevented them from registering the fact that the candle was no longer burning. Then it would begin to seem unintelligible, as the thoughts of a former existence must be to a reincarnate spirit.” (Proust 1)

“Usually you are nestled under the blankets and the house is empty. Sometimes the moon is missing and beyond the windows the low, gray ceiling seems approachable. Its darks light dims in degrees depending on the density of clouds and you fall back into that which gets reconstructed as metaphor.” (Rankine 1)

Both examples channel a somewhat universal experience within the very act of departing the night’s dream and thusly thrusting into the day’s waking abstraction. We can sense a transitive subjectivity that’s neither oneiric, nor fully cogent. This is why at the earliest interactions with their respective readers both narrators are yet to be defined by their gender, ethnicity or social class. Of course, Rankine promptly goes into an specific memory that posits her as a black female in the new millennium’s United Sates while Proust own descend into the past brings us to the particular experience of a white male in France’s fin de siècle. They take different routes with markedly different purposes, sure, yet they also relate in terms of literary form.

When we ponder the unquestionably political purpose of Citizen as social discourse and criticism, the presence of Judith Butler and James Baldwin are especially felt. In fact, Rankine explicitly cites them both. Of Butler she extracts the concept of addressability, analyzing the manner in which the dominating rhetoric overtly establishes a hierarchy of who’s to be valuable and how the discarded Others should thus be handled. In Violence, Mourning, Politics Butler denounces this very practice, for example pondering on the way Palestinian victims are invisibilized in the mainstream media; the story of the newspaper that refused to publish an obituary of a bombing in Palestine is particularly poignant in this regard. Rankine sees a parallel in the reactions to Trayvon Martin’s murder and how this act affected every other black person’s subsequent interactions with any type of police force, or even mere police presence.

Sadly, this type of dealings are nothing new in the United States and deceased figures of American black thought loom over Rankine’s text, James Baldwin probably being the most prescient. In fact, even beyond the quotation of Baldwin’s maxim that “the purpose of art is to lay bare the questions hidden by the answers”, Citizen as a whole could be seen as a type of actualization of The Fire Next Time. The specificities of each author’s historical contexts, there’s a 51 year gap between both books, only serves to reinforce how time has been unable to change the structure of exclusionary identity politics. Whether through Baldwin’s ruminations on the symbolic quality of Elijah Muhammad as both person and image or Rankine’s criticizing of the media’s unjust treatment of Serena Williams’s supposedly inappropriate attitude, The Fire Next Time and Citizenequally succeed by writing about what would be current in the eras they were respectively published.

There’s much ground to cover, I’ve certainly only scratched the surface on the transtextual qualities of Citizen. Maybe I’ll do a more exhaustive version in the future, by their very nature web publications merit constant revisions, but for now I’ll conclude by mentioning what I surmise is the crucial artistic influence of Rankine’s work: Chris Marker, quite possibly the single most important figure in the evolution of the poetic documentary as an art form in itself.

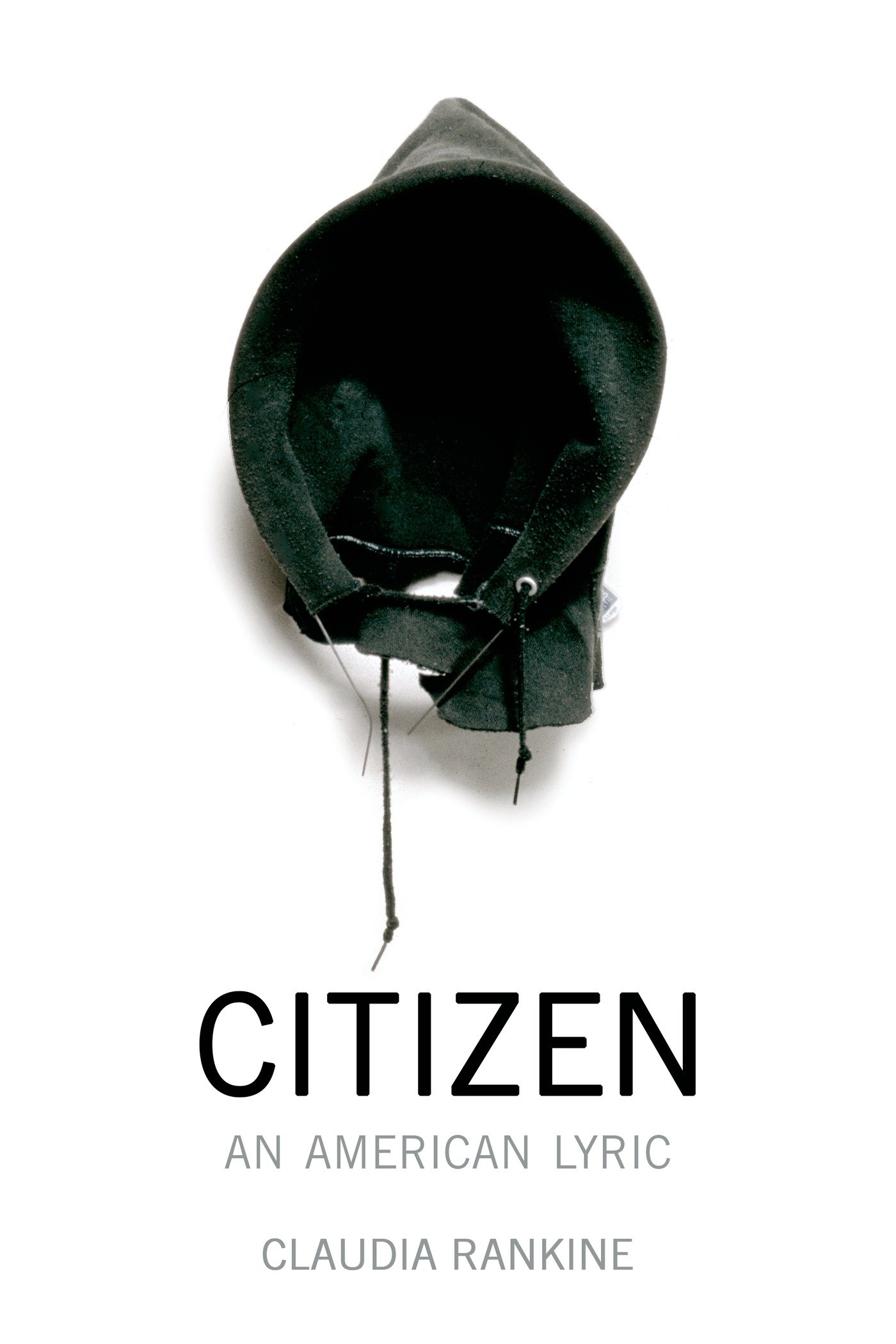

Even before the formal beginning of the book, Citizen’s very first epigraph comes from Chris Marker’s groundbreaking documentary Sans Soleil. “If they don’t see happiness in the picture, at least they’ll see the black”, a phrase that in the context of the film refers to an ontological absence, the black in question is the space between shots in the montage, and which Rankine repurposes as a metaphor of the skin as a visual marking for exclusion, referring to the way mainstream culture relates blackness to otherness. Here she uses a film term in a literary manner, but further in Citizen she also does the inverse by interjecting mixed media into and beyond the main text.

The pictures, photos, videos and overall visual component of Citizenbear a strong Marker influence. To give just one example, while seeing Rankine’s short film Situation 7, which dramatizes one of the sections of the book dealing with the politics of seating during a train ride, I thought of Marker’s final documentary, Chats perchés, where he captures the early 2000s artistic manifestations against the Iraq war and subsequently gets enamored of a recurring anonymous graffiti of a grinning cat, and his photographic exhibition Passengers, where he transposes classic painted portraits with photographs of a regular subway journey.

But I digress. As I mentioned before all these authors and texts could keep me writing and writing. For now I’ll conclude by intuiting that Claudia Rankine’s intent and expression is much more than a series of printed words in a book. Citizen should be read and reread as part of a continuing political and cultural transtextuality. None of this exists in a void. It’s up to us readers to find the already existing correspondences, while also making sure to impinge ourselves even a little bit. Simultaneously students and teachers, we can only coexist by transforming ourselves from spectatorship into artistry and vice versa.

Lista de referencias:

Baldwin, James. (1983). The Fire Next Time. New York: Dell Publishing.

Butler, Judith. (2004). "Violence, Mourning, Politics." Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. New York: Verso Books, pp. 19-49.

Genette, Gérard. (1997). Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree (Stages). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Marker, Chris. (2011). Passengers. New York: Peter Blum Edition.

Proust, Marcel. (2004). Swann’s Way. New York: Penguin Books.

Rankine, Claudia. (2014). Citizen: An American Lyric. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press.

Lista de imágenes:

1. Alec Longstreth, "Blackness Visible", 2014.

2. Portada de Citizen (Graywolf Press), de Claudia Rankine.

3. Ricardo DeAratanha, Claudia Rankine sentada en el salón de su casa en New Haven, 2015.